The last three years have been nothing short of a major challenge for the wider cultural industry, especially for music festivals. The COVID-19 pandemic itself, and the public health regulations implemented to contain it, but also the uncertainty of the future – including the audience’s individual plans, artists’ possibility of travel, governmental recommendations and orders for safety, and even organisers’ own health – made it difficult to plan any major cultural event, especially one gathering dozens of artists and thousands of viewers on a campsite. And this was the case with Pol’and’Rock Festival, the biggest music festival in Poland. After my two previous posts about the event’s ways of dealing with the pandemic situation – first almost completely online, then by limiting the audience capacity – it was finally possible to be on the festival campsite in person, listening to live music and experiencing all the elements – both pleasant and not-so-pleasant – that make up the experience of this unique festival. Even though the shadow of the pandemic, as well as the ongoing war in Ukraine, was hanging over the concerts and their viewers, it is hard to deny that Pol’and’Rock Festival 2022 was an intense celebration of a “return to normality” after two editions in limbo.

This unique situation of the “return to normality” lends a very strong argument to applying the perspective of ritual studies to the 2022 edition of Pol’and’Rock Festival. While this framework is widely used in analyses of cyclical cultural events, this year’s case is arguably even more suitable than usual. The festival is no longer only a break from the everyday, a fertile ground for anti-structure to emerge in unusual circumstances, but a genuine mark of returning to a changed reality, a re-integration into the structure – even if the structure in question is the carnivalesque fun time outside of everyday chores. In a way, a two-fold relation of normal and exceptional, mundane and celebratory, structural and anti-structural can be seen in the 28th Pol’and’Rock.

On the one hand, corresponding to the usual perception of music festivals in anthropological research, Pol’and’Rock is still a liminoidal situation (Turner, 1982). People gather in a secluded area to have fun away from their day to day chores, to celebrate being together, and even to suspend the usual rules of being in society – the mud baths again appear the most obvious example of this last aspect. On the other hand, however, it was apparent among all of the participants in the event – audience, organisers and artists alike – that they viewed this year’s concerts as a break from a long lasting and much less pleasant, but still liminal situation of the pandemic years. In this sense, the possibility to have fun, be carnally close to others, appears as a celebration of the normal, of what people want their usual existence to be (Pielichaty, 2015; Turner, 1983). From this perspective, the 2022 edition of Pol’and’Rock was a carnival situation par excellence – a festive, anti-structural, liminoidal occasion, that is essentially a celebration of the sordid everyday. The experience of finally being able to dance without fear of touching was the celebrated normal after two years of awkward handwaves and mediated communication.

None of the above should obscure the fact that if the 28th Pol’and’Rock festival was a return to normal after a liminal period, the normal returned to was a changed one. Even though the festival, as with all open air summertime events in Poland during the pandemic, has been treated with a relative leniency – in comparison to meetings in a closed space during the autumnal flu season – some marks of lasting changes in people’s attitude towards public health were still visible. The influence of the COVID-19 pandemic was still present in the way Pol’and’Rock 2022 was organised, although once again, in a very carnivalesque way. The most obvious example of it was the occasional person walking around the campsite, mockingly telling people to cover their faces or keep the 2 metres distance from each other. This can serve as a prime example of reliving the traumatic event through turning the order of the abnormal / normal couplet upside down, something very much in the spirit of carnival. Other influences of the pandemic were, however, visible in a generally heightened awareness of health issues for all participants, even if not directly referring to viral contractions. As far as this last aspect is concerned, perhaps the only notable change is the presence of disinfectant gels in the campsite’s Lidl shop. Across the event’s social media there were regular reminders to cover one’s head and stay hydrated, as the temperatures during the event were very high. Perhaps the most notable change caused by the pandemic is the way in which the definition of festival community has altered. This is because people watching the online transmissions of concerts were embraced as a valid part of the audience, even if this was acknowledged mainly by a discursive distinction between the people on the campsite and those staying indoors.

Another major change was an apparent increase in ecological awareness related to the problems music festivals often cause in this regard. The action “It’s getting clean” (Zaraz będzie czysto, a variation on the festival’s password of “It’s getting dark”), even though first organised in 2018, was particularly visible this year. Not only does it encourage people to chip in on a crowdfunding action to cover the costs of cleaning the campsite, it is also targeted at simply asking people to clean up after themselves, once again showing the organisation’s reliance on people’s individual responsibility. This visibility is well illustrated by the Instagram filters – besides the yearly variation of the festival’s theme, there was also a mini-game where people could “catch” falling junk.

The 28th Pol’and’Rock Festival was organised in a new location of Czaplinek in north-western Poland, which, according to the main organiser Jurek Owsiak is going to remain its partner at least for another year. As always, the festival had a year’s leading theme present throughout the advertisements and merchandise. This time, the call was timely indeed – “No War”, and the expression of support for Ukrainians were present both on the stages and among the audience. Despite the lingering awareness of global problems, the artists, audience and organisers of Pol’and’Rock tried to maintain as joyful an atmosphere as possible, allowing people to once again experience the nothing short of a carnivalesque ritual of having fun together, distancing themselves from if not reversing the concerns of their everyday lives.

Even while the 28th Pol’and’Rock Festival can be seen primarily as a “return” for long-standing participants, it is also worth acknowledging that for many people it was the first time they attended the festival. To a certain extent, this has been historically part of the event’s ethos, because of its itinerant nature. Since the festival was – again, after last year’s low fee meant to cover the sanitation costs – completely free, and also took place in a new location, new people could attend this big happening. For many of them this could have been simply a matter of age, as three years ago they were simply too young to attend. Ending this short description of the 28th Pol’and’Rock Festival, one group for which the event was less a celebration of freedom than a shock from the organisational issues needs to be named and congratulated for their perseverance in helping others have their fun – the railway workers. Faced with singing across the train, occasional inebriation and spilled beer, and perhaps most shockingly the very number of people arriving in Czaplinek and nearby towns, they tried their best to accommodate them with more frequent trains and by checking the tickets of people as quickly as possible.

On the whole, the 2022 edition of Pol’and’Rock Festival fits in with many characteristics of a ritual of return, of reintegration into the normal. Even while the shadow of the last two years was still hanging over the organisation, accompanied by arguably an even more worrisome aspect of war, it was evident that people went there to once again feel a part of the joyful normality.

References

Pielichaty, H. (2015) Festival space: gender, liminality and the carnivalesque. International Journal of Event and Festival Management, 6(3), 235–250.

Turner, V. (1982) Celebration. Studies in Festivity and Ritual. Smithsonian Institution Press.

Turner, V. (1983) Carnaval in Rio: Dionysian Drama in an Industrializing Society. In F. E. Manning (Ed.), The Celebration of Society: Perspectives on Contemporary Cultural Performance (pp. 103–124). Bowling Green University Popular Press.

]]>Irish Arts Festival Archive Co-coordinator, University College Dublin

Since 2016, I have worked as a festival studies researcher in an academic context, while also acting as Festival Advisor to the Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon. This dual role, and my previous professional experience as a festival maker, puts me in a very particular locus within the Irish festival ecology; one that afforded me a privileged perspective on the challenges facing festivals during the last two years. Working independently as a researcher, I have completed a number of in-depth studies of the changing operating models of festivals in Ireland during the Covid-19 pandemic (Teevan 2021; 2020). Concurrent with this work, I was tasked by the Arts Council with curating and moderating webinars that were aimed at helping the festival community sustain their organisations during this unprecedented time -Talking Festivals (May/June 2020) and Pathways 2021 (March/April 2021). Together these documents form part of an important archive of the Irish festival sector’s struggles and evolution during this time. It was in this context that Dr Aileen Dillane and Dr Sarah Raine invited me to write a guest blog for Festiversities – to provide an overview of Irish festivals’ metamorphosis over the last two years.

In Ireland, as elsewhere, the number and diversity of arts festivals grew exponentially over the last forty years. While not all festivals that include the arts in their programming are funded, it is a measure of the growth and importance of festivals in this country that support for festivals by The Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon increased from 12 events in 1977 (The Arts Council 1978) to 173 in 2018 (The Arts Council 2019).

Before the arrival of the pandemic, there were few weekends in the year that did not have an arts festival somewhere in the country, with a diversity of festival types catering for a wide variety of interests. In the field of music, which is the focus of the Festiversities research, this ranged from the world renowned Wexford International Opera Festival, to the Clonakilty Guitar Festival, Limerick Jazz Festival, Claremorris Folk Festival, Cork International Choral Festival, Killaloe Chamber Music Festival and any number of festivals that focused on Irish traditional music, like Masters of Tradition in Bantry and Traidphicnic in Connemara. The diversity of this sector is not confined to artform or genre differences, but extends to the operating models of the festival organisations. So, while some of these festivals have full-time professional management teams working all year round, others are managed by professional arts workers on short-term or part-time contracts, and still others are run by voluntary committees.

Over the last eighteen months I have observed Irish arts festival organisations with awe and admiration, as they worked tirelessly to operate in the face of unimaginable obstacles presented by governmental restrictions imposed to stop the spread of Covid-19. During this time the festival community demonstrated resilience and innovation as they cancelled, reimagined and reworked plans to enable festival events to take place in spite of the restrictions, all the while learning new skills and adapting their operating models to accommodate the transformed and everchanging reality within which they found themselves. As documented by the Festiversities research teams, similar stories of resilience and creative management were happening across Europe. In my own research, I documented organisational changes required to enable four case study festivals to successfully present programmatic content online, the challenges these organisations had to overcome to operate effectively during this period and the impact this period had on organisational planning for the future (Teevan 2021; 2020).

While it is still too soon to determine with any degree of certainty the longer-term implications for festivals of the upheaval caused by the pandemic, it is certain that the impact of the last eighteen months will have long-term consequences for this sector. For example, there is evidence to suggest that the digital dissemination of work that was so critical to festivals – particularly in 2020 when severe lockdown prohibited live performances of any kind – will remain part of many festivals operating models. This can be justified in terms of the wider access online presentation of programming facilitates, but it is also probable that the festival makers and artists that have developed digital skills, will be keen to persist with the use of these tools and platforms, which have opened up new creative possibilities and facilitated connections with new audiences.

The restriction on indoor live performances in Ireland during much of 2021 and a series of grant schemes for funding outdoor events, encouraged many festival organisations to discover and develop new venues in parks and other public spaces. Unable to run concerts as per usual in the Town Hall Theatre and Abbeystrewry Church, Skibbereen Arts Festival (an annual multidisciplinary arts festival in West Cork) had a stage built in a small enclosed park at the edge of town where it ran a series of concerts. The venue proved to be ideal, and Festival Manager Declan McCarthy admitted that without the restrictions they may never have discovered this facility. Taking advantage of a capital investment funding programme for outdoor infrastructure, Galway Local Authority Arts Office purchased a stretch tent with capacity to accommodate a stage and a seated audience of 300 people. According to Arts Officer Sharon O’Grady, this was a long-term investment aimed at being able to provide a weather proof performance facility for festivals throughout the county for years to come.

Another noticeable development in the festival sector in Ireland over the last eighteen months has been a much greater tendency for festivals to work together. Within days of the first lockdown being announced in March 2020, festival organisations realised the need to share intelligence to deal with the unprecedented challenges that they were facing. Over the following months different groupings of festivals began meeting online, some self-organised, some organised by Local Authority Arts Officers, others facilitated by the Arts Council. Over the following year different conflagrations of festivals emerged as consortia intent on sharing marketing, infrastructural and/or human resources.

As festivals embark on putting in place plans for 2022, the shadow of Covid -19 still hangs ominously in the ether demanding that festivals remain flexible in their planning. However, this planning is being done by organisations with very different capacities to the organisations that faced the first lockdown. Resourced with digital skills, newly discovered venues and flexible infrastructure, and working in solidarity with other festivals has greatly strengthened the arts festival ecology in Ireland.

While recognising the value and importance of these gains, it is also important to acknowledge the burden the pandemic has placed on festival makers, and the potential for long-term damage to this important feature of Irish social and cultural life. In September 2021 when restrictions had eased, I was able to travel to a number of festivals around Ireland. After over a year without live entertainment, there was great excitement among the public to be out at cultural events, and in particular, being able to discuss the artworks experienced with friends and strangers. Among the event organisers however, the mood was not so ebullient. Without doubt there was satisfaction in presenting events and seeing the public’s delight, however, there was also, in many of the organisers I encountered, a weariness that was troubling.

Over the previous eighteen months working in isolation much of the time, festival makers had invested time and energy learning new skills while undertaking additional administrative and logistical juggling to keep pace with changing restrictions. They also had to strengthen health and safety protocols to ensure a safe space for artists to work and for the public to enjoy the work. Whether professionally or voluntarily run, the human resources of festival organisations are invariably stretched, reliant on a small group of committed individuals. While the committed individuals I met were, in the inimitable fashion of festival organisers, being positive about the future, there were also signals of distress, with festivals reporting concerns about fatigue and burnout. Among the voluntary run festivals, which are a crucial part of the festival ecology in Ireland, there were reports of a noticeable drop off in people’s availability, resulting in an unsustainable situation where more work was being undertaken by fewer people.

Attending the EFA (European Festivals Association) Summit in Galway (22-24 Nov 2021), I had the opportunity to meet with representatives from European festivals and festival resource organisations. The European festival makers spoke enthusiastically about opportunities the pandemic had provided, with many noting that lockdown afforded them time to re-evaluate their organisation’s mission. In particular, this enabled festival organisations to integrate issues of sustainability and inclusivity more centrally into their operating models. The exponential rise in the use of digital technologies by festivals was another recurrent theme. While the value of transmitting festival programming online was applauded in terms of the access it provided, opinions differed about the merit of digital dissemination in a festival context, where there is an expectation of a ‘concentration in time and place’ that digital media does not replicate. Mirroring the Irish festival situation, there were also many delegates who spoke about fatigue due to the extended duration of the pandemic and the demands of working with such a high level of insecurity.

In conclusion, I would add my voice to those who have rightly applauded the resilience and resourcefulness of festival organisers in villages, towns and cities throughout Europe. However, I would also caution that due care and attention be given to consider the long-term sustainability of the sector at this time, and in particular the importance of supporting the people that deliver for us each year these indispensable social and cultural events.

References

Teevan, D. (2021) ‘Online and on land: an examination of Irish arts festivals’ response to Covid-19’. Irish Journal of Arts Management and Cultural Policy, 8: 133 – 157.

Teevan, D. (2020) Digital needs?: supporting arts festivals’ transition to programming a blend of live and digital experiences. 11th Annual ENCATC Conference Proceedings, Cultural management and policy in a post digital world – navigating uncertainty, pp. 129-147.

The Arts Council (1978) Annual Report 1977. Dublin: The Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

The Arts Council (2019) Annual Report 2018. Dublin: The Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon.

]]>University of Limerick, Ireland.

As researchers interested in European music festivals, public spaces, and diversity, the past twenty months have been disruptive, challenging and at times emotional. Like the festival professionals we had hoped to work closely with during FestiVersities, we had to transform our plans, create new strategies of engagement and production, and to ask ourselves what really lay at the heart of the project, pandemic or no. Our emerging answer to this final question coalesces around the concepts of collaboration, shared practice, compassion, creativity, and optimism.

In attending the Irish Arts Council Pathways 2021 webinar series run between March and May 2021, it was clear to us that these five elements were threaded throughout both the intentions for and contents of the sensitively facilitated panel discussions. Curated and hosted by Dr David Teevan, (Festivals Advisor to the Arts Council) and under the stewardship of Karl Wallace of the Arts Council, Pathways 2021 aimed to provide a space for critical conversations between festival makers and their stakeholders. With festivals cancelled across Ireland and public events paused for over eighteen months, never has such a space been needed more, not simply to touch base and connect with likeminded people but also to find strategies to cope and, potentially, thrive.

In our research to date, we have noticed an increased level of communication between festival teams as they struggle to make sense of conflicting information, ongoing uncertainty, and a prevailing sense of care for their communities. Platforms like Zoom and Skype have become a lifeline, bringing together festivals – in Dublin and Chicago, Cork and Copenhagen, Limerick and Liverpool – as they reimagine their forms, processes, and function in a very new and different world. In the case of the Pathways 2021 series, participants in each seminar were warmly welcomed in by David and the panel team, and made to feel that their experiences and creative solutions to the challenges of COVID-19 were valued and of value to other arts professionals. Having “attended” many arts sector virtual panels and workshops throughout the pandemic, Pathways 2021 offered festival and arts professionals access to a wider and more diverse network. Equally important and new was the manner in which Pathways offered a space for both sharing everyday practices and for considering larger philosophical questions.

Inge Ceustermans of The Festival Academy pointed out (Session 1, March 10th 2021) that different people in different places experienced the impact of lockdown to varying degrees, but that many had used the opportunity to consider the efficacy of the digital festival platform, not just in communicating with older audiences but also in finding new ones. Such speculations were married with ruminations on sustainability and care, in particular of artists. John Crumlish (Galway International Arts Festival) asked attendees to consider “what happens when you take the place away” from festival experiences (Session 2, March 24th 2021). In a similar theme, Avril Stanley – the director of one of our FestiVersities festival sites, Body & Soul (panel 2) –asked, “how do you take the festival experience and the beauty of an area, create a narrative, and turn it into a story that has meaning?”. And in bridging theoretical questions and everyday practices, Ruth McGowan used examples from Dublin Fringe Festival to consider possible models for creating tactile, sensory and intimate audience experiences in digital spaces (Session 3, April 7th 2021). Each of the four panel sessions were well balanced in terms of art form, location, festival model and experience, including a wide range of arts festivals from across (and beyond) Ireland. For many of the attendees, the Pathways 2021 panels offered a number of creative, successful, and well-considered models for future practice and inspiration for Arts Council Ireland funding applications, as many of the represented festivals reported on previously funded events.

Pathways 2021 was unafraid to venture into terrain that is often seen as anathema to ‘creatives’, with Conor McAndrews from Accenture (Session 1) offering strategies from RND and future planning (typically applied to corporations) for the festival context in order to enable better decision making. The presentation focussed on grounding any business model in human-centric design, that ultimately had considerable resonance with the attendees, generating excitement about how to apply scenario-making for future resilience.

It was this seamless blending of arts industry, non-arts expertise, and scholarship that was particularly compelling in this suite of seminars. Common issues were highlighted and framed through research and theory, in addition to experience, by David Teevan, who (in Session 3), borrowing from Victor Turner (1969), summarised the focus of the festival as creating a space for “communitas”. A well-used term by scholars, but the (2012) work of anthropologist Edith Turner is particularly apt here: she views communitas as an “inspired fellowship” and an instigator of collective joy. Illustrated by the examples provided in Pathways 2021, both fellowship and joy persisted in the festival offerings of 2020 and 2021.

Reflecting on engaging with audience and performers, Pathways considered both the local and the global. Lorraine Maye (Session 4, April 21st 2021) talked through event examples that were rooted in local communities and spoke to the ways in which Cork Midsummer Festival had reimagined annual events during national lockdowns. Although creating the same levels of trust with local and international partners over Zoom calls was explored as an issue throughout the Pathways sessions, it was clear to see that many festivals had mindfully engaged with local and international audiences, partners, and performers in compelling and efficacious ways.

In our own FestiVersities research, we are interested in tracking the ways in which issues of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion have continued to thread through the activities and future plans of festivals during the COVID-19 pandemic. This was most clearly explored in Padraig Naughton’s (Arts and Disability Ireland) presentation, with Naughton observing that a movement online does not naturally translate into increased access for all (Session 3). Whilst few online performances have offered audio description, captioned events, included sign language interpreters, or organized relaxed performances, in our own research we have experienced festival platforms that do offer a range of access-focused personalisation options, to include those which support neurodivergent audience members. However, as Padraig made clear to us all, digital spaces and festival models offer both solutions and further issues in relation to access, and that we must all be careful to question our assumptions about who is included and excluded. And when the time comes to pivot back to live offerings, we should all be asking what elements could we maintain for optimum inclusion.

As any associated professional or research will attest, the role of the festival is multifarious; from providing an immersive and multisensory audience experience to acting as a seasonal employer. Most significantly for the context within which we all find ourselves this year, the festival as an instigator of positive change within society was clearly articulated by both the framing of the Pathways 2021 series and throughout the presentations. A pervasive and declared emphasis on supporting performers and suppliers by many of the festivals demonstrated a keen awareness of the difficult times that many have faced. In a similar vein, issues of sustainability were raised, with the pandemic period representing an opportunity to establish new practices and processes with reduced carbon footprints or that allowed festivals to establish more secure positions within wider arts ecologies. Amidst all the continued uncertainty and worry, it was heartening to be immersed in a community that looks forward to not only a post-pandemic world, but a world of increasingly mindful and considered festival production which places collaboration, sharing practice, compassion, creativity, and optimism at its core.

References

Turner, E. (2012) Communitas: The anthropology of collective joy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

Turner, V. (1969) The Ritual Process: Structure and anti-structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing.

]]>Uniwersytet Jagiellonski, Poland

The 27th edition of Pol’and’Rock Festival (formerly known as Station Woodstock) in 2021 took place in very unique circumstances. The COVID-19 pandemic may not be over yet, but in Poland many restrictions have been loosened in light of the vaccination program, and cultural events are coming back to life. In the case of Pol’and’Rock – “the most beautiful festival in the world” – this meant a break from last year’s very harsh restrictions, but continuation of those still in place. Most importantly, this included a limited audience (up to 20,000 people, including 250 without valid vaccination certificates) which meant that for the first time in the festival’s nearly thirty year history it was necessary to buy tickets. Unfortunately, I did not gain entry. Fortunately, this allowed me a glimpse into the less formal side of how the festival’s fans were coping with a situation of ‘twofold liminality’ they found themselves in.

The underlying theoretical perspective framing this description of Pol’and’Rock’s 27th edition is that of liminality as developed by Victor Turner. This applies both to the general situation of the event – standing in between last year’s very strict limitations and a slow “return to normality” – and the unique case of those people who could only gain partial access to the concerts. At the same time, music festivals themselves were frequently analyzed through the lens of liminality and ritual, including by Turner (1982) himself. Classically, liminality has been understood as a state “in between”. The liminal phase of a ritual is characterized as a time when a person, usually a participant of a ritual of passage, is already beyond a pre-liminal stage, such as childhood, but not yet accepted as a member of a post-liminal stage, for example adulthood.

In the context depicted here, pre-liminality is understood as, on the one hand, the state of the COVID-19 pandemic and the accompanying restrictions (as a side note, it is worth noting that they themselves can be viewed as a liminal stage), while the post-liminal phase is the hopeful time following its end. Of course, this framing is somewhat questionable. For example, there is no specific moment in time or a threshold in the number of vaccinated people that would mark the definite end of the coronavirus epidemic, and an increasing number of medical specialists are pointing out that many of the behaviours developed in this time are likely to be here to stay. Nevertheless, for a layperson’s imagination “return to normality” would be marked by being once again allowed to participate in social gatherings and cultural events, and as such here it is understood in this way. In this context, liminality is viewed as the unique circumstances when some events are allowed to take place, but many restrictions are still in place. On the other hand, this text also focuses on the group of people who would like to partake in the festive ritual but could not join the actual festival with its spatially restricted campsite and good access to live music. With this framework in mind, it seems appropriate to move onto the description of the festival itself, as well as the unique group analyzed here.

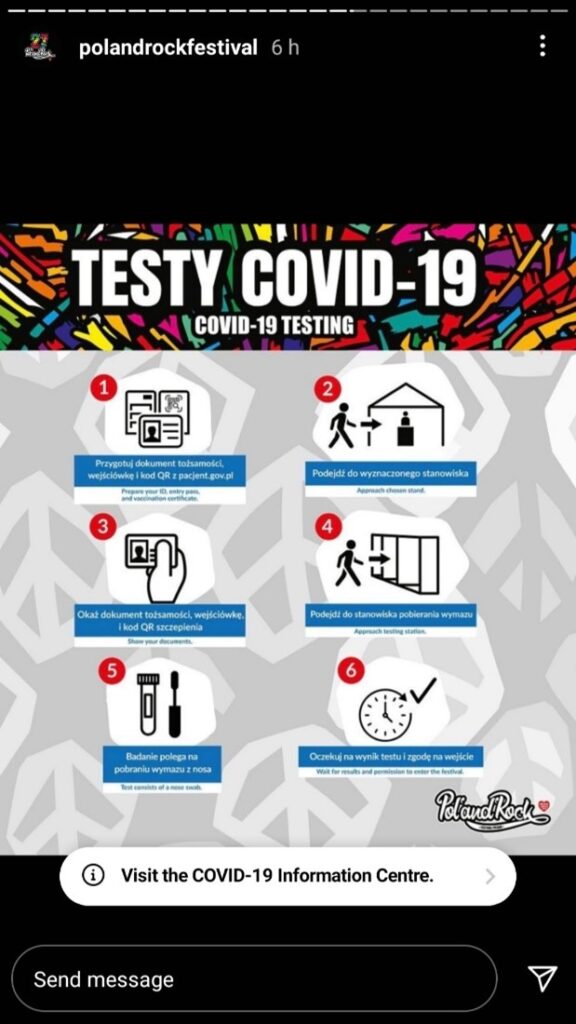

The 27th Pol’and’Rock Festival took place between 29th and 31st July 2021 in a new location, Płoty in West Pomerania. Through strict formal entry procedures, the event was very well protected from anyone with coronavirus. Most importantly, for the first time in the famously free festival’s history tickets were introduced, and identified with the name and surname of the person entering to prevent them being resold outside the official capacity. The entry fees were low at 50 zlotys (around 12 Euros) and were distributed in a number corresponding to those currently allowed at social gatherings in Poland, that is 20,000 participants, including 250 unvaccinated people. Additionally, everyone including those with a vaccination certificate was tested for the virus before entering for free, but anyone leaving and re-entering the campsite was required to take the test again, but this time with a payment. It should be noted that the festival infrastructure was well organized, especially considering that it was the first time it took place in a new location. Special trains were travelling between Szczecin and Kołobrzeg, and the festival-goers were picked up from the train station by buses, which would take them to a spot a short distance away from the actual festival space. The line-up of Pol’and’Rock included performers both from Poland – such as Dżem, Raz Dwa Trzy, Renata Przemyk, Pidżama Porno or Kroke – and from all across the world, including Morgane Ji and Slift, with the latter giving their first concert in Poland (Zespoły, z którymi planujemy spotkanie na Festiwalu, n.d.).

Unfortunately, I could not obtain a ticket. While the organizers were insisting that watching and interacting with the event online – on YouTube, Discord or Twitch – is “just as valid” a form of participation in the festival, and indeed those on stage would make callouts to what was written online. It appears that for many this type of participation proved insufficient, or felt somehow incomplete. The advantages of this sorry circumstance proved to be quite rewarding for me, though. First, I probably would have never taken interest in the contests organized by the festival’s partners, which turned out to be an interesting way of activating the potential audience’s creativity. Those who would like to try their chance at winning the tickets were asked to, for example, create unique wishes for an unknown participant or say what they cannot imagine their summer without. Secondly, and more importantly, I had a glimpse into the grey area which emerged around Pol’and’Rock. Many people would come without a ticket, hoping to get one by the entrance or to be allowed into the campsite without one, but were firmly, though politely, turned away by the volunteers. In fact, they would even suggest to me that I join some of the people already present in their “alternative party”. Indeed, those standing by the queue would dance, play their own music or just stand by the fence, screaming their disappointment in the direction of the main stage. Additionally, the citizens of Płoty quickly noticed that the unfortunate non-attendants might prove a goldmine, offering a private campsite right by the fence of the festival. In various online discussions there emerged a suggestion that an alternative Pol’and’Rock be organized in Kostrzyn, the place where it took place over the last few years, though if this initiative succeeded, it left few lasting marks in the community. Last but not least, it should be mentioned that Station Jesus – a festival organized as a Christian or even evangelistic event alternative – also took place this year. Some of the participants would migrate between Station Jesus and the former Station Woodstock, interacting with those hopelessly standing by the latter’s entrance. Their input was rarely as welcome as it was this year.

The people described above are characterized by a strong sense of subjective identification with Pol’and’Rock community. Many of the interviewees stated that they partook in earlier editions, which is what prompted them to travel to the festival site, even without assurance of entering the main festival, though it should be noted that most of them declared that they live in relative proximity to Płoty (for example, in the same voivodship). Similarly, and this time encouraged by the organizers, a sense of community could be found among online participants of the 2021 edition of Pol’and’Rock Festival. In this case, the unique phenomenon of the pandemic could be observed, namely that of the unity of time replacing the unity of space, which usually creates the liminal character of a music event. Of course, this liminality is limited given the circumstances of the event, with participants devoting their time to listening to the festival while also taking part in their everyday activities. This is largely the source of the title of this blog entry. For the organizers, it was crucial to ‘manage’ the liminality of Pol’and’Rock as much as it was possible. Firstly, the Turnerian anti-structure typical of music festivals was much smaller than usual due to the ever-present pandemic restrictions. Secondly, and partially contradicting the former statement, there were visible attempts at making the restrictions of this liminal stage between pandemic and post-pandemic times as unobtrusive as possible. Lastly, despite encouraging partying by the campsite’s entry, it was necessary to limit such non-participation, so that a general sense of the event’s uniqueness was maintained. On the whole, however, the 27th edition of Pol’and’Rock proved to be a truly exceptional experience, not in the least because of people’s willingness to join the event – to partake in this liminality – limited as it might be.

References

Turner, V. (1982) Celebration. Studies in Festivity and Ritual. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Zespoły, z którymi planujemy spotkanie na Festiwalu. (n.d.). Accessed August 30, 2021, from https://polandrockfestival.pl/kto-zagra

]]>Erasmus University, Rotterdam

After more than a year of COVID-19 we are looking back at a year of innovation, of creative solutions of festival organizers and audiences alike. We saw audiences rebuilding past festival experiences, and we saw organizers come up with new ways for audiences to celebrate their festival at home or with distance. Eurovision is no exception. The festival was supposed to be held in Rotterdam in 2020 but due to the measures back then could not be realized. This year, constraints due to COVID are still present. Nevertheless, Rotterdam has found its way to, as it goes in the city’s slogan, ‘make it happen’. Through online live shows, for example by DJ Afrojack at the iconic bridge de Hef or Duncan Laurence, the winner of Eurovision 2019, at de Maassilo, but also through online tours around the city, talkshows, drag shows and online yoga classes the city is trying to show itself to the world and offer their audiences an experience supposed to resemble a festival experience. All of this can be watched by anyone with an internet connection, laptop or smartphone, from anywhere in the world.

However, Eurovision is not only a well-established event that showcases a host city to the world (see for example Andersson and Niedomysl, 2008), it is often also seen as fostering a sense of belonging and civic pride for locals (Wolther, 2012). But what is happening in Rotterdam that is visible to locals and what image of the city is showcased? Where can we see and feel that a major event like Eurovision is taking place in Rotterdam, knowing that crowds will be largely absent? In this blog, we will take you on a walk through the city of Rotterdam during Eurovision 2021 with these questions in the back of our heads.

The spaces and people that make an urban space a festival city can still be found during Eurovision week. It is not difficult to spot the giant blue microphone made from recycled PET-material from Rotterdam waters at Central Station, or the big purple flags with Eurovision logo’s all across the center of the city. The banners at the entrance of metro stations, the stairs taking you to the platform having been decorated, as well as posters alongside the roads and across Erasmus Bridge cannot be missed. At other places, hardly any visual markers give away the presence of Eurovision. Some festival markers are present around city hall at Coolsingel in the center of the city, such as a car with the Eurovision logo parked at the front, or the banners and flags the building has been decorated with. Walking alongside the river, you would not notice anything unusual up until getting to the well-known sight of the Erasmus Bridge, where purple Eurovision flags and banners across the bridge signal the presence of the festival.

Eurovision is seen as a good occasion to showcase what a city is about. For Rotterdam, as it appears from videos presenting the city in the Eurovision village, this is about innovation and entrepreneurship, sustainability and, most relevant to our project: wanting to show the diversity present within the city. This becomes particularly visible when we cross the Bijenkorf, where the shop window has been filled with mannequins dressed in Eurovision themed clothing and Angisas (traditional Surinamese headscarfs).

These Angisas have been created by Rotterdam based designer Selita Klas and were an essential part of the outfits according to the city dresser Madje Vollaers, who we got to speak to after seeing the designs. The outfits as a whole are meant to emphasize the theme ‘’LOVE’’, which is meant to resemble the diversity present in Rotterdam. The traditional Surinamese headscarfs made by Selita can be seen as an example where the city uses the opportunity to represent and portray elements from different ethnic groups living in the city. This edition of Eurovision could be said to be important for Surinamese representation in particular, with Jeangu Macrooy, a singer of Surinamese descent, representing the country and singing in English and Sranantongo. Even though the celebration of the Eurovision Festival cannot be done as usual, Madje and Selita both stated that they feel more connected to the festival due to their work for the project.

We continue our walk deeper into the centre where we notice a strange absence of the festival at de Binnenrotte, the location where the Eurovision village was supposed to take place and which is highly contrasting to the same location in the digital sphere. Where you see the stage, the bright colours of the festival venue, the small figures resembling people walking around the festival site and hear the festival buzz in the online environment, nothing except some stickers on de Markthal and a digital poster reveal anything out of the ordinary happening there in real life.

The closer we get to Ahoy, the only place where crowds will be allowed at some points this week, the more we start to sense the festival. Not only because the number of visual cues increase, with banners surrounding the metro station close to Ahoy and the mural made of Jeangu Macrooy across Ahoy as well as the art installation made by several street artists in front of the concert venue. The sense of the festival is increasing here with the stimulation of other senses, such as the traffic light playing ‘Waterloo’ when you cross the road and the figure within the traffic light actually starting to dance (as well as some people crossing). We also see more and more people who seem to be engaged with the festival in one way or another: from volunteers wearing Eurovision sweaters, to a woman in the metro wearing a Eurovision face mask and tote bag; from a local bartender wearing a Eurovision face mask, to a small group of guys wearing pirate clothing and delegates from different countries in traditional clothing taking pictures with the Eurovision scarf.

The presence and non-presence of the festival in the city feels striking. We assume that many people will be celebrating this Eurovision week from their homes, behind their computers and tv screens, and we see people taking pictures with the microphone at central station or the banners at Erasmus Bridge. Without the possibility to draw in huge crowds except for Ahoy with the semi-finals and final, organizers and city officials have been able to move around restrictions while retaining some sense of the festival presence. Allowing for the possibility of online celebration for people across the world and the mostly visual representation of the festival in the city, we could not have asked for better ways to continue feeling the presence of the festival in Rotterdam.

References

Andersson, I. and Niedomysl, T. (2010) Clamour for glamour? City competition for hosting the Swedish tryouts to the Eurovision Song Contest. Tijdschrift voor economische en sociale geografie, 101(2): 111-125.

Wolther, I. (2012) More than just music: the seven dimensions of the Eurovision Song Contest. Popular Music, 165-171.

]]>University of Limerick, Ireland

Sitting on sofas in different cities with our phones clutched in our hands, the 2021 Cork International Choral Festival playing on our laptops, was not what any of us had in mind when planning for festival fieldwork in pre-pandemic days. Having not yet met in ‘real life’ due to lockdowns and restrictions, our team dynamic has been up to this point fostered over Zoom and shared documents. On the last weekend of April into early May 2021, instead of soaking up the festival atmosphere, exchanging notes on our embodied experience of a particular city and a number of venues, and taking a moment to sit together and chat at the end of the day (maybe over a pint), we are sat at our respective homes sharing our thoughts over WhatsApp. And in this we are not alone.

For five days over the May Bank (public) Holiday weekend, choirs and choral music fans from across the world immersed themselves in the virtual offerings of Cork International Choral’s first digital festival. Perhaps they too chatted via messaging with friends or choirmates, sharing their critiques and their favourites to win each competition. For over a year now, people across the world have increasingly relied upon technologies and mediated interactions in order to access culture, community and a world beyond their immediate circumstances. For those who do have access to internet and devices (and the technical know-how to use them), digital intimacies and a feeling of togetherness whilst physically apart have developed and become a central part of our everyday. Festival teams are searching for new ways of connecting with their audiences and their performers; audiences are fashioning a new sense of togetherness and shared experience; creatives are reimagining their work in a new digital space; and researchers are trying to make sense of it all, to ask useful questions, and to consider what society more widely can learn from this period of disruption and uncertainty.

That is not to say that we have not travelled anywhere this year. Indeed, as our individual physical worlds have contracted our imaginations have expanded, transporting our minds (if not our bodies) to a range of imagined places and virtual experiences. With increased reliance upon virtual meetings, many of us have noticed an increased level of international collaboration and cooperation, with new networks developing and essential practices shared as we all attempt to cope with a previously inconceivable reality. Some of us have even made new friends, met new partners, gained new teammates online, developing different ways of getting to know each other and to make things – festivals, research projects, family parties, first dates – happen in a way which makes them meaningful. This year has really pushed the idea of ‘community’ to an extreme. Yet here we are, stubbornly creating communities and redefining what we mean by publics, public space and cultural encounters.

As an ethnographic research project, our understanding of these emerging digital intimacies begins with our own. The 2021 Cork International Choral Festival was not the first virtual event for either of us, not by a long shot. It came at the tail end of year of digital festivals, conferences, industry panel discussions, and Arts Council webinar series, varied offerings which had been exhausting and liberatory in equal measure. We had already experienced a whole world of talks and performances ripe for engagement and analysis, but forever from the four walls of our homes. Yet this festival was different – the first fieldwork event for our new team and an opportunity to get to grips with how a choral festival could be translated to the digital with, as Fabian Holt has pointed out “a new type of festival cinematography…with marketing videos for social media consumption” (2020: 241). As audience members, we explored the platform and waited patiently for each event to go ‘live’, we scheduled our meals and dog walks around the programme, and we eagerly anticipated the awards ceremony and chose our favourites. As researchers, we undertook short bursts of textual analysis, shared notes on initial insights and questions to ask the festival team, and we jotted down quotes from a variety of expert speakers (judges, performers, industry professionals). At the intersection of these two roles, we got to know each other as people, sharing jokes and little snapshots of our lives and interests beyond work. In real time but over WhatsApp, we shared our emotive responses to beautiful pieces of music, all the while conscious of the fact that we were just two members of an international audience. These moments created an opportunity for digital intimacies. Between the two of us as a newly formed team, and between ourselves and a wider community made-up of people we knew, names and profile photos we could see on the festival platform, and many others that we had to imagine, their existence revealed by the viewer number which waxed and waned over the five days.

Through surveys and emails, Zoom interviews and focus groups, we will now place these autoethnographic reflections within a wider ethnographic context, and ask what the emerging insights might mean for the future of music festivals and, in this instance, choral music. More importantly, through our work we aim to explore whether and how these practices and experiences have had an impact upon the conceptualisation and realities of inclusion and exclusion at music festivals in Ireland and how these findings may compare in other European contexts.

Like the music industries and festive practices that we are studying, many challenges lie ahead. It is clear that alongside new forms of digital intimacies, new ways of place-making and value construction are at play, complex processes which also intersect with shared notions of authenticity and value, genre and tradition, identity and belonging. Building on our previous work, many past theoretical frameworks may be useful in framing these experiences and in articulating their meaning, yet we must be increasingly reflexive as we attempt to make sense of a confusing and fragmented period. Equally, we need to take stock and ask many important questions. For us as researchers, we are already wondering what a sustainable and adaptable music ethnography methodology looks like, especially in a possible future of reduced international travel, Zoom interviews, and greater resource awareness? And reflecting upon the music industries in Ireland, we aim to ask big questions relating to inclusion and exclusion, and to highlight and problematise a return to the structures and processes that have historically facilitated gender discrimination, ableism, and racism in the production and consumption of music. As Bruno Latour clearly states, this period of disruption offers an opportunity for all:

If everything has stopped, and all cards can be put on the table, they can be turned, selected, triaged, rejected for ever, or indeed, accelerated forwards. Now is the time for the annual stock-take. When common sense asks us to ‘start production up again as quickly as possible’, we have to shout back, ‘Absolutely not!’ The last thing to do is repeat the exact same thing we were doing before. (2020: 2)

References

Holt, F. (2020) Everyone Loves Live Music: A Theory of Performance Institutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Latour, B. (2020) “What protective measures can you think of so we don’t go back to the pre-crisis production model?”. Available at: http://www.bruno-latour.fr/node/853.html

]]>Uniwersytet Jagiellonski, Poland

A year ago, in March 2020, Poland entered the first lockdown, which influenced the cultural sector in general and the music festival scene specifically. At the time, it was still believed that the critical situation would not last long, leaving festival organisers in a state of uncertainty as to how they should proceed with the events planned for 2020. Cracow a member of UNESCO Creative Cities Network with its nearly 100 festivals organised annually, many on an international scale, had to face these new circumstances. The organisers were forced to cancel or redefine the form of their events, as well as look for new ways of communicating with audiences. The three festivals that we observed (EtnoKraków/Crossroads, Sacrum Profanum, and Unsound) responded to the pandemic circumstances in a different way.

Following the governmental restrictions, the EtnoKraków/Crossroads festival postponed the date of the 2020 edition a couple of times, waiting until the last moment to decide when, where and how to organise it. Eventually, it was delayed for two months and involved visible limitations due to sanitary reasons, resulting in a hybrid form: live concerts with sanitary restrictions were combined with radio transmissions of previous editions’ concerts, and online streaming via Facebook and on their webpage. The Unsound Festival’s first reaction was to cancel the 2020 edition, but shortly later the organisers decided to change its format, to launch a crowdfunding campaign, and to go online with a different programme encompassing less music and more talks. The theme of the 2020 edition was “Intermission”, referring to a break caused by the pandemic, “a period starkly separating before from after”.

Following the first governmental announcement about COVID -19 restrictions concerning the festival sector, the Sacrum Profanum festival organisers made a decision about a total change of their festival form, treating it as an occasion for experimentation. They moved the whole event to the virtual space (using a special VOD platform ‘Kraków Play’ created to share cultural content during the pandemic), but with a brand new cycle of live concerts pre-recorded in various festival locations specifically for the 2020 edition, with artists and sound technicians present on the spot. The “only” missing element was the physical presence of the public. The duration of the event was also prolonged from one week to one month, turning it into a “slow festival”, as stated by the organisers. The examples of the above mentioned festivals shows that there are different models of a “hybrid festival” where the “hybridity” may concern: the space, transmission channels, geographic dimension, and content.

Although the “hybrid events” are not a completely new phenomenon, it is only now that they become necessary to keep festivals from falling apart during the pandemic. Rather importantly, the majority of respondents to Event Manager Blog’s survey declared that they wanted to maintain the online audience after the pandemic crisis is over. If hybrid events are indeed here to stay, it seems important to study how they are experienced by all participants of the festival community: artists, organisers, and last by not least, the audience.

Hybrid festival spaces may be described as spaces where different types of festival experience can occur simultaneously: live/real and virtual; collective/shared and individual; public and private/intimate. The issue of hybrid spaces as domains of intercultural relations had already been studied before the COVID-19 emergency changed the understanding of participation in culture and cultural exchange. Leszek Korporowicz (2016; 2017) claims that hybrid spaces are areas of constant transgressions and creative potential, especially if they also allow for different cultures to interact. Moreover, this transgressive potential is also linked to the technological characteristics underlying the virtual-/cyber-space, which in turn influence the mental and social states of their users. Most importantly, they are spaces where “physical distances lose their importance in favour of semiotic ‘distances’”. As a result, the very understanding of space – especially in its symbolic and informational aspects – changes, becoming increasingly “contextual, hybrid and multi-dimensional”. Korporowicz (2016:19) suggests that all of these characteristics allow not only for the broadening of cultural spaces’ borders, but made them very easy to cross: “They are full of “holes” or “gateways,” and, in equal measure, overlays and synergies that shift in the world of global information flow, and consequently of a new configuration of communities defined by their participation in the network society” (Ibid.: 20). Are music festivals, especially those taking place in hybrid spaces, such gateways? Another definition of hybridity can be provided in the context of the mass media. The term “hybrid” refers there to a complex intermedia dynamic between mainstream news media and social media, as well as the complicated circulations between messages and actors, and the recombination of media on a variety of media platforms. Sumiala et al (2016: 98) describe hybrid media events as “media events whose significance for media professionals, politicians, and non-elites is being reconfigured by the growth of social media”. The hybrid festivals’ formula can also be analysed through the concept of “time-space distanciation” introduced by Anthony Giddens (1991). According to him, the advance in communication technologies caused the stretching of social relations and made the remote interactions a significant feature of everyday life. As a consequence, the interconnectivity and interdependencies have increased, as can be seen from the example of the online festival communities, connecting people from many corners of the world.

The Unsound Festival’s organisers made a direct reference to hybrid realities by including the theme of hybridity in one of the debates during Unsound Lab, a special workshop for people wishing to start a career in music management. The discussion “Online/offline – hybrid possibilities” focused on the immaterial future of music and the role of streamed music events. They also organised an experiment with the participation of the audience and invited people to place multiple online-devices (including those archaic ones) around their apartments and simultaneously listen to the same performance. The idea was to produce a completely new sonic effect, a “Corona-style multichannel-audio experience”.

The observation of the 2020 editions of the selected festivals allows us to enumerate the following COVID -19 challenges and opportunities the organizers were and are still dealing with:

A) Reorganization and new uses of the festival space, including the appearance of cyber spaces, “time-space distanciation”, and a blurring of private/public sphere(s). On a more theoretical level, it can be said that in hybrid and virtual events, all or part of the role usually fulfilled by space is overtaken by time: rather than by meeting in the same place, any sense of community is created by mass communication at the same time. The example of the Sacrum Profanum organisers showed a fresh attitude to the virtual space: they tried to treat the network as a place of artistic activities, rather than merely the means of reflecting them. The new formula allowed them to showcase concerts in interiors that could not be used in the traditional model. This has given them the impetus for change: in future editions, they plan to reduce the number of listeners in order to give them the opportunity to participate in smaller events taking place in original locations (beyond mass reach), as well as to go to the backstage and see how the event is produced in real time.

B) New forms of organiser-artist-audience cooperation where the festival experience is turned into a “mediated experience”. The artists and debate participants had no or a limited ability to interact with the audience or gauge their reactions, especially in the case of pre-recorded performances in the Sacrum Profanum festival. Consequently, the organisers had to explore the online mediums’ affordances to deal with this barrier: for Unsound, this meant the occasion to finally fulfil their long term plan of publishing a book of essays and an album of songs recorded for the festival – both of which are available in the traditional (indeed, vinyl!) formats, as well as digital downloads. However, probably the most interesting examples of hybridity in performance came as a direct result of a Coronavirus infection suffered at the time by the festival’s artistic director, Jan Słowiński. Firstly, he had to coordinate a live event entirely virtually, which may be usual in the preparation stage, but is less common during the festival. Secondly, his wife Joanna, who is also a singer and was isolating with her husband, participated in the performance with the Sokół Orchestra via an online connection . This also meant that the musicians had to coordinate their live playing with her virtual vocals – and it must be stated that they did this flawlessly.

The pandemic crisis had its financial aspect which proved quite painful for the cultural sector, though it must be noted that the festivals we analysed were in a relatively good situation, as they do not rely fully on ticket sales. Still, the usual financing from central and municipal administration was largely cut, leading the organisers to look for alternative sources of money. In Unsound’s case this meant an online crowdfunding action, which turned out to be very successful, showing their festival audience’s strong sense of solidarity with the event. On the other hand, the organisers of Sacrum Profanum Festival decided to work exclusively with Polish artists to support native performers, as the individual artists were also affected by the pandemic restrictions.

C) New understanding of openness/exclusion. Online events are available theoretically for a limitless public, but in practice participation is restrained by technological skills and resources. Among those who do have them, new patterns of accessibility can be observed: the virtual/hybrid concerts are available for people who would be excluded from the traditional live format (especially people with disabilities and those who can’t afford to travel to festival site). Additionally, there may be increased participation from people who would usually be indecisive on whether they want to go to a given event, as monetary and time costs are much lower in such circumstances (the case of Sacrum Profanum, a festival of experimental and modern classical music).

D) Rethinking active/passive participation. While the intrusion of the festival into private homes has its disadvantages, it may also pose an opportunity for the audience to take a more active part in the event’s life. The most striking example of this is the case of Unsound being crowdfunded by its fans. While some prosumptive behaviours – in the sense of consuming/experiencing the concert through the audience’s own creations and activities – are possible and indeed frequent in traditional, live concert circumstances, in the hybrid situation they become the only widely available way to engage (or at least feel engaged) with the artists and other viewers. Whether it is a photograph of oneself while watching the event, a comment under the transmission or a handmade painting on the festival theme, the real-time online audience activities become much more important for the maintenance of festival atmosphere. The Sacrum Profanum festival also provided other forms of online interaction with the public: Cracow’s soundwalks for children, DIY digital workshops on making musical instruments or an interactive composition with alternative variations to be chosen/voted by the audience watching the event via Play Kraków platform.

E) New opportunities for (virtual) cultural exchange. The example of the Unsound festival audience showed that its online actions – on Facebook and Discord – were aimed at maintaining a sense of community. Live commentators are eager to share where they come from and non-Polish speakers are usually welcomed by local participants, often offering help in “moving around” the virtual stages. It can be seen as a realisation of Manuel Castells (2010) network society, with the festival itself serving as the central “node” of communication, surrounded by many multidirectional exchanges between the participants from different cultures.

Probably the most profound change that emerges in the festival sphere due to the emergence of hybrid festivals is a change of the very meaning of “liveness”. A festival can be a “live” event even in a virtual space, where the interactions within the festival community and real-time reactions of the public occur through digital channels.

As Paweł Potoroczyn – an EFA member and culture manager – states, “festivals are ideas in work, and not brands”. The emergency situation and atypical conditions often make space for new (courageous) ideas, experiments, and “extravagance”, as was manifested during the restrictions during the time of the pandemic. The current circumstances remind us that the concept of ‘liminality’ is inscribed into the phenomenon of (music) festivals, and especially to festival communities. The new festival formats that appeared as a consequence of Covid -19 are unquestionably a manifestation of organisational creativity, even though for some researchers and festival sector specialists, like Robert Piaskowski, nothing can replace the real, material (physical) event and that “emotion that spreads in the crowd and not only in the network”.

References

Castells, M. (2010) Społeczeństwo sieci (M. Marody (trans.); 2nd ed.), Warszawa.

Giddens, A. (1991) Modernity and self-identity: Self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Korporowicz, L. (2017). Extended cultures : towards a discursive theory of hybrid space. In A. Duszak, A. Jabłoński, & A. Leńko-Szymańska (Eds.) East-Asian and Central-European encounters in discourse analysis and translation, Instytut Lingwistyki Stosowanej, WLS UW, pp. 13-31.

Korporowicz, L. (2016) ‘Intercultural Space’, Politeja 5 (44): 17-33.

Solaris, J. (2020) The Future of Events Is Definitely Hybrid: What Will They Why Hybrid Events Are Here to Stay. https://www.eventmanagerblog.com/future-is-hybrid-events

Sumiala, J., Tikka, M., Huhtamäki, J., & Valaskavi, K. (2016) ‘#JeSuisCharlie: Towards a Multi-Method Study of Hybrid Media Events’, Media and Communication, 4 (4): 97-108.

]]>University of Bristol, UK

‘It is with great regret, we must announce that this year’s Glastonbury Festival will not take place, and that this will be another enforced fallow year for us. In spite of our efforts to move Heaven & Earth, it has become clear that we simply will not be able to make the Festival happen this year. We are so sorry to let you all down.’ (21 January 2021)

Will the summer of 2021 offer a beacon of hope for festivals? After a somewhat subdued Christmas and New Year with very little socialising with friends and family, summer was looked to as the time when the pandemic would be behind us. The assumption was that normalcy would return, social gatherings of any size would be feasible, friends and families reunited, and public spaces could again be filled with people, celebration, music and dance. It turns out, ‘summer’s lease hath all too short a date…’ For many, the above statement from Worthy Farm signalled that summer ‘21 may all be over before it has even begun.

This time last year, Glastonbury (along with other very large music and sporting events) were the first to cancel, because it requires many months of significant on-site construction of its infrastructure and securing that its complex supply-chains are in place. At the recent DCMS (Digital, Culture, Media & Sport) select committee on The Future of UK Music Festivals, Paul Reed from the Association of Independent Festivals (AIF) stated that smaller music festivals and events could leave their decisions until March. However, without a government-backed insurance scheme in place to support their business activity in the lead-up to this summer’s events, another cancellation would push many festivals further into precarious financial positions with the future of (some) music festivals looking rather bleak.

Despite the dark, foreboding clouds hanging over music festivals again this year, it is worth remembering what many festivals did in 2020 to recapture the festival community and to remake the festival space in alternative forms whether online or through other spaces and creative practices. Glastonbury was able to present a multimedia set of alternate events in 2020 in conjunction with the BBC, but can the same be repeated this year? Will the same technologies of nostalgia and collectivity work again in a second fallow festival year?

Watching Bowie perform on the Pyramid Stage in 2000 during GlastoAtHome 2020, and hearing him reminisce about playing there in 1971 created many intersecting layers of representations and memories of Glastonbury (and of Bowie who died in 2016). Those of us who weren’t there in 2000 or 1971 imagined how both performances were for him and the audience. Doing so enabled us to join a wider, yet largely unknown, community of festival goers, producers, workers and artists who for years have contributed to making one of the biggest music events in the world happen. It shows how virtual festivals create music’s ‘vivid presence’ (Schutz 1976) – that is, they enable a dispersed audience to share a fleeting portion of time, across a vast, networked space.

Glastonbury is a truly iconic festival, an integral part of the British summer, and indebted to the spirit, myth and reality of the original 1969 Woodstock festival, like most if not all, large scale music festivals, according to Bennett (2020:216). Its impressive 50-year-old history spans from the 1970 hippie and free festival movement – when a fledgling, unknown Bowie first appeared, through the 1990s when dance music was introduced, to the 21st century becoming one of the most famous commercial music festivals of all time, adding pop and hip hop to its musical fabric, and ensuring a plentiful supply of the eccentric, the grotesque, the strange and spectacular. With over 200,000 people on site each year, Glastonbury festival embodies the social and economic history of the changes observed in the festival industry. It is one of the most important cultural phenomena in British music history.

With large gatherings of people in fields cancelled last summer however, as an alternative the festival website offered links to numerous playlists, documentaries, activist talks, streaming dance classes, poetry, and access to its archives. The message on the website was clear, it asked people to stay away from Worthy Farm, suggesting that many might have been tempted to ‘camp out on the land’ and ‘get their soul free’ on the weekend it was due to take place. Instead, thousands of people celebrated the 50th anniversary of Glastonbury online. Social media was full of stories from previous years with hashtags (e.g. #GlastoAtHome) bringing pictures and memories from festivalgoers and artists together. Given the importance of the festival, people were invited to re-live or imagine the experiences of the past 50 years through a virtual network of the festival’s community, mediated and narrated by the BBC. The BBC provided access to past headliners with at least 10 million views on the BBC iPlayer alone.

But, for all of the multisensory experiences of art, theatre, dance, and humanity on offer at the event itself on Worthy Farm, music was the main item on the virtual menu for that weekend. It was music that united us with our friends, it was music that sutured different times, diverse memories, imaginations and spaces together. GlastoAtHome showed us what it means to experience music across time and beyond a physical festival space, as Smith (1979:16) argues music is ‘a continual becoming, in which the modalities of present, past and future are brought together not spatially only but as the emergence … of the musical phenomenon’. Music, therefore, according to David Hesmondhalgh, creates possibilities for ‘life-enhancing forms of collectivity, not only in co-present situations but across space and time’ in mediated ones (2013:85). The collective emotive experience of music at festivals creates and reinforces a sense of belonging to the festival community. Indeed, in our research, all festival organizers emphasized the importance of the community of people who produce and consume the festival. And this collectivity is not only constructed through music but also through the physical space, i.e. face to face encounters with like-minded people, sociabilities, sensory experiences and aesthetics of space. However, the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted festival communities that had been maintained by these temporal proximities. The lack of physical connection meant that music, available in the virtual space, became the only sensory experience through which belonginess could be maintained.

For over twenty years Glastonbury’s community has stretched the temporal and spatial dimension of the festival’s site, with millions of viewers able to watch it live on BBC. But last summer the virtual dimension was the only one that connected people together. The community continued by the collective memory of the festival’s past that has temporarily transformed Glastonbury into a type of a nostalgia festival which expressed longing for the past. As Bennett and Woodward (2014:15) noted, ‘rather than merely celebrating a collective representation of the past, ‘nostalgia’ festivals may also play an important role in helping festivalgoers to define their individual and collective identities in the present’. Nostalgia, in this sense, can be seen as a critical tool (Pickering and Keightley 2006:938), a productive means of creating security, that reinforces the sense of belonging in the times of uncertainty caused by the outbreak of COVID-19. The collective memories in the virtual space made Glastonbury 2020 real, alive, and thriving, while helping to imagine the festival’s future.

Although acknowledging the potential that music has for sociality and community, Hesmondhalgh also reminds us that music can ‘reinforce defensive and even aggressive forms of identity’ (2013:85). As much as we prefer to think of music festivals as enabling people to flourish collectively, they can also create division – we only need to remind ourselves of the Jay-Z ‘Wonderwall’ moment in 2008, where for some, rap had no place on the Pyramid stage, preferring instead a narrow, whitewashed version of headlining guitar acts. Many also remember the tensions surrounding Glastonbury’s changing status and identity in the 1990s – once a safe-haven for travellers and those supporting a free-festival ethos that became an ugly, stand-off with Michael Eavis, Worthy Farm, Pilton Village and the Avon and Somerset Constabulary. Given the increasing popularity, mediation and commercialisation of the festival, organisers were under pressure to secure, protect and refine the festival-going experience for a new generation of festival-goers wanting a shinier, slicker, celebrity encrusted version. And yet, in the virtual space of Glastonbury last year these tensions and divisions were absent as the festival celebrated its diversity showcasing a range of music genres and artists.

The unwelcome, but necessary, decision about the festival’s cancellation in March 2020 was transformed into a positive reimagining of the festival through a range of virtual platforms and spaces enabling a sense of belonging to the festival’s community amidst the loss and trauma of the global pandemic. Unlike smaller or new festivals, large, well-established festivals like Glastonbury did not have to worry about the possible threat to their integrity posed by its furlough last year, given they routinely have breaks so the pastures and land recover from the festival onslaught. However, last year there was hope that music festivals would come back in 2021 and the nostalgic reflection and participation in online festival spaces would be temporary. Will the Glastonbury festival survive another cancellation, or will it go bankrupt?

British music festivals are anxiously waiting the government’s decision about whether they can go ahead. With festivals contributing billions of pounds to the British economy each year, there is hope for the industry to survive, but only with the financial support from the government. Culturally, as the example of the virtual Glastonbury shows, there is a need for festival communities to continue. With significant negative effects of the prolonged pandemic on mental health, belonging to a community is now more important than ever. The emotional responses on social media to the loss of festivals last year demonstrate the resilience of the community. Last year’s Glastonbury’s ‘vivid presence’ constructed virtually through memories of music played an important role in giving hope for the community of artists, organizers and festival goers during the pandemic. But can the community survive another year without the festival? Will another virtual festival be enough to bring people together?

David Bowie is often heralded for his prescient views about the web. In 1999 he said, at this point we had only witnessed ‘the tip of the iceberg’ in terms of its impact on society. Little did he know that in 2020 – and possibly again in 2021 – we would be shown how a vast network of people, times, music, memories and spaces that constitutes Glastonbury could be reimagined and remade through this medium.

References

Bennett, A. (2020) ‘Woodstock 2019: The Spirit of Woodstock in the Post-Risk Era’ Popular Music and Society 43 (2): 216-227.

Bennett, A., Woodward, I. (2014) ‘Festival Spaces, Identity, Experience and Belonging’ in A. Bennett, J. Taylor and I. Woodward (Ed.) The Festivalization of Culture. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2013) Why Music Matters Oxford: Wiley- Blackwell.

Pickering, M., Keightley, E. (2006) ‘The Modalities of Nostalgia’ Current Sociology 54 (6): 919–941.

Schutz, A (1976) Collected Papers II. Studies in Social Theory (ed. A Brodersen). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Smith, F.J. (1979) The Experiencing of Musical Sound: A Prelude to a Phenomenology of Music London: Routledge.

]]>Karolina Golemo and Marta Kupis

Uniwersytet Jagielloński, Poland